One hundred years ago, people were curious about Christmases of the past, too. By the 1920s, Isabella Cowan Rhea (1849-1935) had lived in downtown Knoxville for three quarters of a century, and her family had been in downtown since frontier times. As such, she was considered an authority on local history, and reporters regularly consulted her for stories about “Old-time Knoxville.” Two decades before that, other reporters had done the same with another longtime downtown resident also named Isabella: Isabella Reed Boyd (1831-1907).

A century before newspapers began asking the Isabellas for their stories, the whole week between Christmas Eve and New Year was set aside for holiday observance, with New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day considered as significant, if not an even bigger cause for celebration, as Christmas. The traditional Twelve Days of Christmas, running December 25 through January 6, were taken very seriously as days of socialization and celebration, almost equal measures of a holiday party, a redistribution of wealth from those that had to those that had-not, and an opportunity for merchants and craftspersons to drum up future business with measures of good food and good cheer. The cold, dark winter weather provided a lull which people used to rest, celebrate, and catch up with family, friends, and neighbors. The result was twelve days of merriment, mingling, fire, food, fun, and frequently, alcohol.

With much work and business slowed or suspended, families and friends spent time together and exchanged gifts with each other. Shops shared foods or small premiums with customers and colleagues. Servants and the enslaved could expect to be at rest for increased time, and often, to have access to special foods like chicken, ham, fruit, desserts made with sugar, as well as opportunities to socialize among themselves. New allowances of clothing were traditionally handed out during this period, and sometimes, other small gifts would also be provided.

During this time, people expected to receive visitors and to visit others. Jovial groups would coalesce in streets or around bonfires, usually in the evenings, and travel from house-to-house or farm-to-farm. Groups often “wassailed” or carried warm cider or other beverages with them, caroling and/or offering drinks in exchange for coins or small gifts.

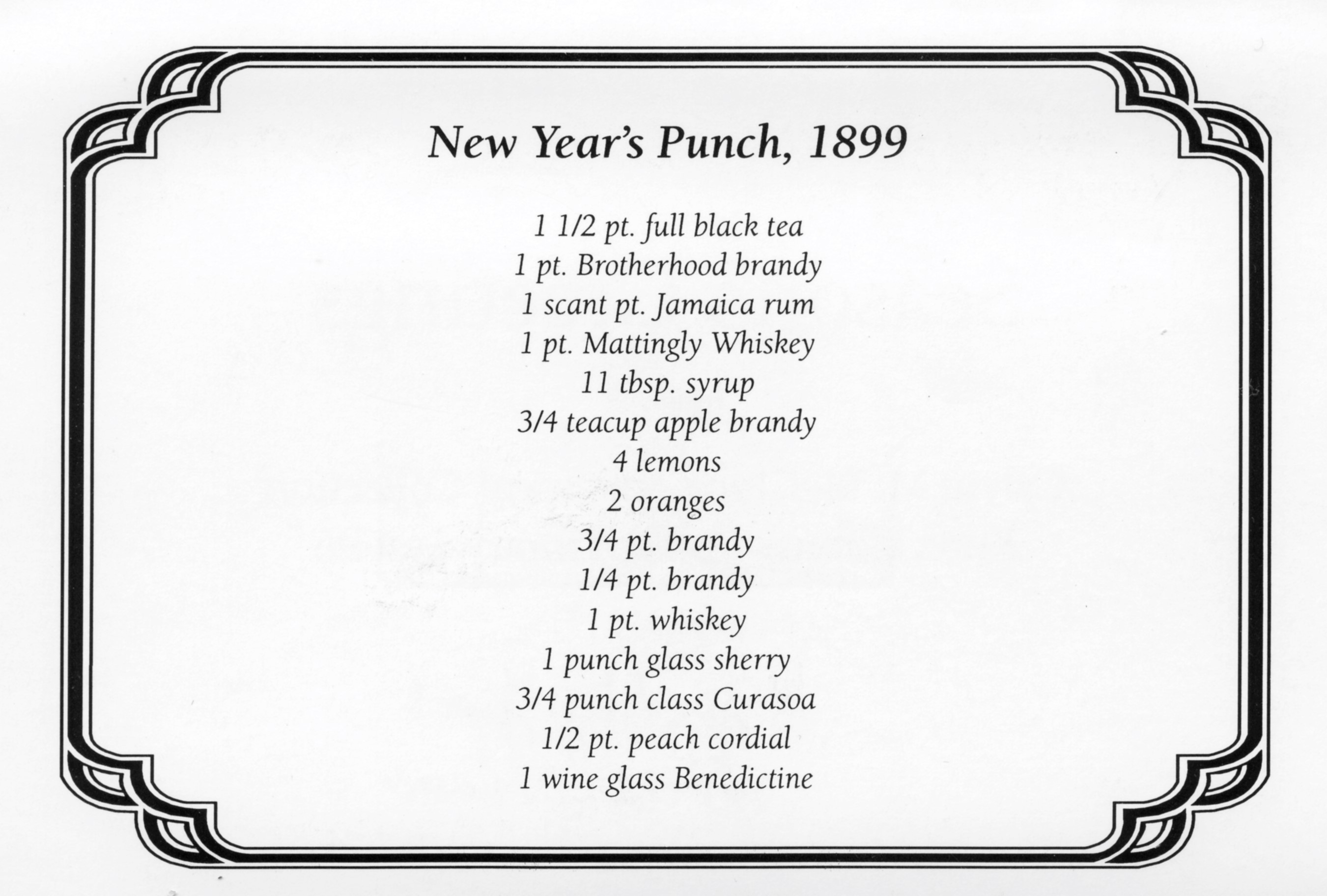

Many shops and households kept tables out over the course of the entire period, stocked with “food boards” of seasonal treats to snack on as well as to serve guests who stopped by. These open houses offered a variety of foods, punches, cakes and entertainments. Hot chocolate was the traditional beverage of the season. Eggnogs, ciders, rum punches and spiced drinks were also popular. Customary foods included doughnuts, cakes, berry pies, holiday candies, and other sweet treats, cheese, bread, pickled oysters, greens, sliced chicken or turkey, and ham spiced with cloves or cinnamon. German settlers served traditional dishes like sausages and sauerkraut. In the deeper South and even up as high as our corner of East Tennessee, a dish of black-eyed peas, rice, and onion (now most commonly called “Hoppin’ John”) became a traditional winter holiday offering.

Isabella Reed Boyd particularly remembered her childhood excitement for chicken salad, wine jellies, boiled custard, and even ice cream. Isabella Cowan Rhea recalled early Knoxvillians’ legendary fondness for a holiday drink called cherry nog, which was apparently an egg nog-type drink, served hot and flavored liberally with whiskey made from cherries. Businessman Gideon Morgan, Jr may have helped create or continue cherry nog’s local popularity. Advertisements from the 1820s show he was constantly in search of cherries for his distillery, up to 300 bushels at a time.

On Gay Street, larger dry goods merchants like brothers Calvin, Gideon and Rufus Morgan or Matthew and Charles McClung, Jr, likely had at least one table of food and drink set up so holiday customers could snack as they shopped. Smaller shopkeepers, like silversmith Samuel Bell, may have done the same, but with display space at more of a premium, it would have been equally common to open their personal home or kitchen to the public, if located in the same building or lot.

Clinch Avenue caterer Edy Minor was always in great demand and her famous cakes and ginger beer would have been served from many food boards over the course of the season. Polly Crush was known for great and abundant fare, so it is likely that her tavern on Gay Street may have served a large traditional spread as well as the sauerkraut and sausages from her Germanic roots, plus the cherry nog which was so locally popular.

Some people were content to gather and simply roam from house to house by the light of lanterns or pine torches while occasionally dropping by open houses to partake of drinks and snacks, but others preferred larger, more active and dynamic events. Knoxvillians and other Americans added their own twists to the traditional festivities of the Old World, including shooting off guns and blowing up anvils. Sometimes churches tried to curb the chaos and revelry by holding “watch nights” or evening services of prayer and reflection, which people could choose to attend instead of roaming parties, fields and streets, but as local minister James Park (1822-1912) later noted, watch nights never quite attracted the same crowds that merrymaking through the darkness did.

Among the local holiday traditions Isabella Rhea remembered were customs which sounded similar to the ancient traditions of “mumming” carried over from Britain. Described for winter holiday events held at Greenfield Village, Henry Ford’s open-air living history museum in Dearborn, Michigan, mumming was similar to the wassailing , but with a rowdier bent, in which men would wear garish costumes and roam the streets or go house-to-house in a fashion somewhat similar to Halloween trick-or-treating. They would be singing, dancing and performing short skits or plays to receive food and drink. Sometimes they would demand warm drink “in kind” from the man of the house and money in addition to or instead of gifts.

Apple howls were popular forms of celebration, particularly at New Year’s Eve, in which people circled an apple tree and hit it with sticks while chanting:

Stand fast root, bear well top

Pray God send us a good howling crop

Every twig, apples big

Every bough, apples enough

Hats full, caps full, full quarter sacks full

Apple howls frequently occurred in conjunction with “bonfire nights” of gathering, dancing, picnicking, music and other merrymaking held in open lots or fields. Torches, firecrackers, and firearms were often involved. Knoxville ordinances did not prohibit, “shooting of guns, rockets, firecrackers, and other fireworks” until after 1831, and in the holiday seasons of years previous all four played a significant part.

Per Isabella Boyd, common sites for these larger gatherings included the open land beyond the north side of Clinch Avenue, “where all was fields of wheat and corn,” “the beautiful oak grove called Gallows Hill” (now Summit Hill), and most especially, Methodist Hill (now East Hill Avenue, around the former Hyatt Regency Hotel), where “a fine grove of oaks” served as the gathering place for many community events, including winter holiday bonfires and barbecues. As she believed few people of the 1900s had witnessed a “real” barbecue, Isabella described the process: The day previous trenches 50 feet long would be dug, 2.5 or 3 feet deep, fires of hickory or oak wood would be built in these trenches, and when they had burned to a good bed of coals, small saplings would be placed across the trenches and meats placed there-on, where it remained all night and until the hour of dinner… frequently basted.

The winter holiday season was also a traditional time for Bible cracking, a fortunetelling practice common in East Tennessee and other parts of the South: Before eating breakfast on New Year’s morning, people would take turns opening a Bible completely at random. Then a verse would be pointed to on the two open pages. The randomly chosen verse was believed to foreshadow the events of the following year for the participants.

Burning of a Yule Log was traditional and common in the fireplaces of Germanic and British homes. In America, almost every other household took part in the custom as well. If followed standardly, the rituals surrounding the Yule Log lasted for at least a week, and often across all 12 nights of the Christmas season, with families burning a portion each night, which would “afterward be placed beneath the bed for good luck, protection against lightning, and, with some irony, fire.”

Per The Encyclopedia of American Folklore (2005), Many had beliefs based on the Yule Log as it burns, and by counting the sparks and such, they seek to discern their fortunes for the new year and beyond… to sit around the Yule Log and tell ghost stories…or card playing…was often done while the Yule Log is burning, all other lights are put out and the candles are lit from the Yule Log by the youngest person present.

These candles were placed on tables and in windows each night to ensure good fortune throughout the year. As the Farmer’s Almanac still proclaims:

A bayberry candle

Burned to the socket

Brings food and larder

And gold to the pocket

While they are lit, the journal Folklore recounted in 1914, all are silent and wish. It is common practice for the wish to be kept a secret. Once the candles are on the table, silence may be broken. They must be allowed to burn themselves out and no other lights may be lit that night.

Tradition says that if you burn a bayberry candle all the way down on New Year’s Eve, you will have good fortune throughout the coming year. The candle should be lit in the evening, when you see the first star appear in the sky. You should not extinguish the candle yourself (bad luck!), it should burn down until after midnight, down to the nub and go out on its own.

On New Year’s Eve, New Englanders and those descended from English origins, like many Gay Street residents, often observed a tradition of letting the old year out and ushering the new year in, during which the head of the family would place the front door open while the clock struck midnight, adding the potential for wind into the mix of people, fire, and smoke.

though surviving newspapers were not able to identify the specific source of ignition, fire was practically everywhere around Knoxville from Christmas through New Year, so it may not be shocking to learn that a house caught fire during that holiday season: the residence and shop of silversmith Samuel Bell.

But The Gay Street Fire of 1827 is a story for another time.

Researched and written by Danette Welch