New Year 1827 rang in not only with a bang, but also with a towering wave of fire whose terror and devastation were burned into the memory of almost everyone who lived through it. It was neither the first nor the last blaze to be remembered by its own generation as “The Gay Street Fire,” but for citizens of the 1820s and 1830s, the Gay Street Fire of 1827 was the one they made the largest impression.

It is quite probable that the “Gay Street Fire of 1827” actually occurred during the last days of 1826. While remembrance of the fire remained sharp for many years, its exact date faded from the story as time passed, and saved news clippings only served to add to the confusion. News of the fire was reported on January 3 in Knoxville and on January 13 in Nashville. Conflicting days and descriptions placed its date variously as the night of Tuesday December 26 into Wednesday December 27, Sunday December 31 into Monday January 1, and Tuesday January 2 into Wednesday January 3. The earliest known coverage in a Knoxville newspaper fixes the date as the night of Tuesday December 26.

Regardless, at some point during this traditional week of holiday festivities, as the town slept and night faded into morning, one of the little fires which still twinkled or smoldered practically everywhere about the town jumped its bounds and took a new flame that grew in intensity until it blazed high and wild and out of control.

People commonly constructed their kitchens as completely separate buildings from their main dwelling houses during this period, precisely because of concerns about fire, and afterward, Knoxvillians suspected this fire had originated in the kitchen at silversmith Samuel Bell’s, where candles and the fireplace had been left burning. Townspeople theorized the night’s high winds entered through a kitchen door left ajar and blew sparks from the fireplace or some other open flame to a surrounding wooden surface. The walls, floor, and furniture were all wooden, and even the ceiling was made of wood beams and soft pine planks, and on one of these surfaces a new flame took hold and grew until it blazed out of control. Whatever the source, by the time the fire began to wake people up, sometime between three and four o’clock in the morning, both Bell’s kitchen and the house beside it were almost completely engulfed in flames.

No one had been sleeping in the kitchen that night, but there were seven people inside the house. Samuel and Eliza Carr Bell were on the first floor, with their toddler daughter and a newborn son who was less than a week old. Betsy Delancey Hankins, a twentysomething silversmith’s daughter who may have been skilled in that art herself, slept on the second floor, as did the two eldest Bell children, five-year-old Eliza and three-year-old Edward. By the time the occupants awakened, they were all hemmed in by fire. When she realized she was surrounded by flames, 26-year old Eliza Carr Bell, who was still injured, ill, and at sick bed from having given birth just days before, grabbed her infant son and dove straight through the closest bedroom window.

Samuel Bell, also 26 at the time, dashed through the flames in the other direction, conquering a closed bedroom door and the blazing stairs to reach the second floor, where he almost immediately realized that he was trapped by a wall of flames. The hall and stairway were both engulfed, and even if he tried to make it back down the stairs, the steps were falling or unlikely to hold.

Their only hope, Samuel Bell shouted to Betsy Delancey, was to jump.

He threw Edward out the front window, snatched little Eliza from Betsy, and did the same. Then, Samuel threw himself out the window.

Betsy Delancey did not immediately follow. Instead, she paused and looked back into the wall of flame.

Neighbors began rousing from sleep, including the Calvin Morgan household across the street and the other members of the Bell household who slept in various spots across other buildings on the lot, among them, Samuel Bell’s twelve-year-old half-brother George Harris and Betsy Delancey Hankins’ little brother Hiram (~1803-1849) and mother Sarah.

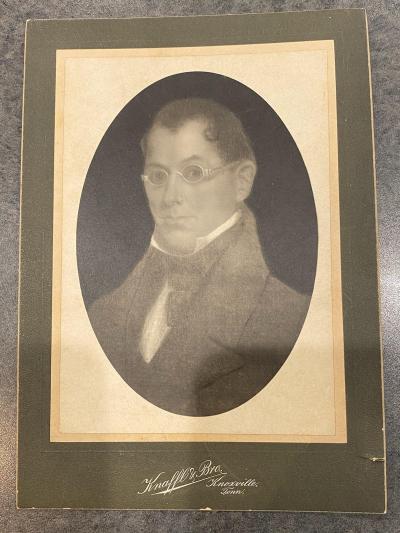

When Calvin Morgan (1773-1851) and his family arrived in Knoxville around 1808, he was concerned by the lack of fire protection and safety. Morgan soon bought a fire engine for the town, but he experienced great difficulty in finding others reliably willing to form a fire company. Thus, he was destined to remain de facto fire captain and fire engine operator for quite a long time. Though volunteer fire companies and volunteer fire captains would come and go, the responsibility still lay with Calvin during the holidays of 1826-27. As soon as he was awakened and alerted to the blaze, Morgan dashed from his bed and ran for the fire engine, accompanied by the young men of his household, and neighbors. Others rushed about raising fire bells and alarms in hopes that more people would awaken and hurry from their homes, hopefully with their required fire buckets in hand.

Eliza Carr Bell, meanwhile, had hit the ground running, almost literally. As soon as she could tumble herself and her newborn up from where they landed, she handed her small son off to the first hands possible and began desperately trying to find a way to re-enter the fiery house.

Her toddler daughter was still inside, awake and crying out.

Samuel Bell had run past his youngest daughter’s bedroom on his frantic dash to the stairs, but he had not paused to go in and get her. The newspapers would say she had been “forgotten,” but it seems more likely that Samuel thought he would be able to reach her and take her out with Betsy, Edward, and Eliza once he got them back down the stairs, not considering, in his panic, that there might not be a way to get back down. It’s also possible that he thought the best chance for his littlest daughter might lie in gambling that another rescuer would be able to enter the first floor and reach her.

Like Eliza Carr Bell, Betsey Delancey Hankins heard the smallest Bell girl’s screams, and with one last look toward the front window and its promise of escape, Betsy made up her mind. She turned to head into the fire.

Some people outside, mostly children, watched through the window, frozen in horror as Betsy’s “silhouette sunk back into the smoke and flames.”

On the ground, a distraught Eliza struggled to free herself from the grip of neighbors who understood that an agonizing death almost certainly awaited anyone who dared to venture back inside.

But the images of the young woman in the window and the sounds of the trapped child were too much for at least two other people to deny. Young court officer Hugh Crozier (1802-1834) and an unidentified man who was conjectured to be Sanford Mason (~1800-1868), who was enslaved by William Swan, but lived at Knoxville in comparative freedom due to the fact he was hired out as a courthouse porter, sprinted into the blazing building to search for them. No access to the upper stories remained and Betsy could not be located, but the men were able to reach the nursery, where they were greeted by the horrific sight of a flaming child, standing trapped in her crib. Hugh snatched her into his arms anyway, and they fled back through the fire.

It being the dead of night and the midst of the winter holiday season, not as many people gathered to the fire as would have been usual and “it was a long time before many people could be awakened.” Of those who did rouse themselves and arrive on the scene, “many did not know what to do as they saw no hopes in saving the girls or the house and no fire company or no one to command.” A significant exception proved to be the women of the town, who, though they took an active role in the bucket brigades at any fire, were noted as particularly active, determined, and at the forefront of the action at this one, perhaps working with an extra measure of grim determination at the thought of Betsy Delancey Hankins, almost certainly dead, but still somewhere inside.

While the Morgan household retrieved and prepped Calvin’s fire engine, the person who stepped in to organize and lead the water bucket lines that would be needed to start the engine and keep it going was a young midwife and mother named Sarah Tinley (1794-1870). The night was extremely windy, and the weather was freezingly cold, and the editor of the Knoxville Enquirer personally observed Sarah Tinley in action at the lead, with her wet clothing already completely frozen to her body but paying the danger no heed. Fear of frostbite did not seem to trouble her or her fellow women on the water lines.

The flames licked high and long, a clear threat to every nearby building or house. With people working each piston by hand, the fire engine cranked to life and began the desperate work of trying to stop the fire from spreading to additional structures.

The fire had already moved to Dr. Joseph C. Strong’s “old medicine shop,” located somewhere behind the Bell house, and it was quickly becoming engulfed as well. A group of young men which may have included George Harris, the younger Morgan brothers, and brothers William and Andrew Park snapped into action to pull down the nearby cheesehouse and smokehouse to keep them from catching fire as well as to create an empty space to act as a buffer between the fire and other buildings.

In hopes of retarding the effects of embers that flew along on the heavy winds, Calvin Morgan used the engine to spray down all the buildings and flammable surfaces within reach. The strategy worked, because “the night was so cold, the water froze where it fell, and was a better preventative than even wet blankets could have been.” The ice that formed from the spraying water and the vigilant stamping out with wet blankets of every ember that took hold on the house of Daniel McMullen both saved his home and stopped the spread of the fire in that direction.

McMullen’s kinsman Thomas Miller emerged as another hero of the fire, and he would later receive extra praise from the town for his efforts. Under his direction, the wooden roofs of the Strong house and the Strong and McMullen stables were manned and given the same treatment, successfully stopping the fire’s spread. Still, it would be a long time after daylight before matters were judged under control.

Despite the valiant efforts of Hugh Crozier and (probably) Sanford Mason, there was no saving the younger Bell daughter. Her burns were so severe that she died just a few minutes after their unlikely escape from the blazing house. Their actions and experiences in the fire would soon turn Crozier’s path from law to medicine and Mason from comparative to official freedom, as well as seal his position in the courthouse for the rest of his life.

Sarah Tinley and other women continued to work grimly through the darkness and into the light of the morning. When the ruins cooled enough to walk among them, they sifted the ashes thoroughly in search of some sign of Betsy Delancey, but the fire had burned hot, intense, and long, and “only a small vestige of her was found amid the general ruins.” The Bells lost at least one child and every single possession.

The landings from the upper window had not gone smoothly. Samuel may have inadvertently fallen on top of little Edward. Whatever happened, both father and son received unspecified injuries that were described as painful and serious. The younger Eliza Bell was reported as the only family member from inside the house who escaped without severe injuries from the flames or the falls. We do not know exactly what kinds of injuries Mr. or Mrs. Bell or the two other children received, but if burns were involved, it may be significant to note that Edward Bell did not marry until near the end of his life.

Today, Samuel Bell is remembered by Texas history afficionados, knife scholars and silver collectors as the premier pioneer silversmith and knife maker of San Antonio, and his half-brother George Washington Harris carved out his own place in the history of Southern literature, but the small Miss Bell lost in the fire remained unnamed. So did the baby boy who Eliza Carr Bell carried from the fire. Evidence shows he was not her next-known son James, so it seems probable that the Bells lost this infant shortly after the fire as well, and like his sister, his name does not seem to have been preserved among the surviving records.

In the wake of the fire, Knoxville would authorize a public cistern to be built and connected to “a suitably sized hydrant on Gay Street.” The fire also spurred an immediate town-wide inspection of all chimneys and orders to rebuild all ones judged hazardous, as well as a short-lived organization of what would be called “the Knoxville Vigilance Fire Company.” It was not until 1859, however, that newly elected mayor James Churchwell Luttrell spearheaded the city’s purchase of modern firefighting apparatus to replace Calvin Morgan’s pre-1808 engine, then took initial steps to form a lasting municipal fire company. It may not have been a coincidence that Mayor Luttrell’s wife was the former Eliza Bell, who was still best-known to Knoxvillians as the little girl who survived the Gay Street Fire of 1827.

Researched and written by Danette Welch